By BRIAN DEVINE

The best way for defenses to contain Met outfielder Michael Conforto is to put a full Ted Williams shift on against him. When three infielders were aligned to the right of second base, Conforto’s BABIP on short line drives and groundballs dropped to .189 last season.

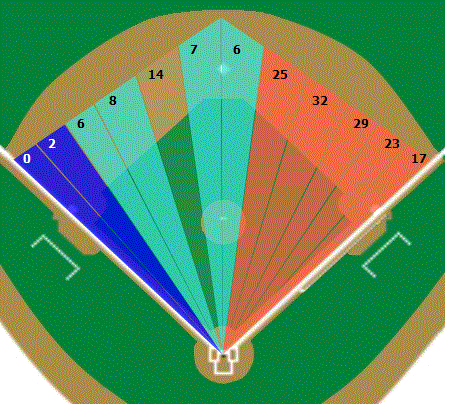

Like many left-handed power hitters, Conforto is susceptible to the shift because he hits the ball to the right side of the infield at a high rate. The 26-year-old outfielder pulled 78 percent of his short liners and ground balls last season, so that explains why the full shift worked so successfully against him. Below is his ground ball/line drive distribution.

Partial shifts, however, have proven to be ineffective against Conforto. When two infielders were aligned significantly out of position, Conforto had a .375 BABIP last season (12-for-40). While a BABIP this high against partial shifts certainly isn’t sustainable, it demonstrates that the partial shifts don’t work against him, which has been the case his entire career.

Conforto entered 2019 with a career .301 BABIP on short line drives and groundballs against partial shifts, but he owns a .198 BABIP against full shifts. These numbers indicate that teams should abandon the partial shift against Conforto, and that they should use the full shift against him more frequently.

A promising sign for Conforto is that he is now committed to adjusting his approach. Working this spring with the Mets’ new hitting coach Chili Davis, Conforto is trying to hit to the opposite field against the shift.

Davis wants Conforto, and the rest of the team, to take a more situational and contact oriented approach. Conforto might be the Met for whom this is most important.

Davis’ thinking represents a change in philosophy from previous Mets’ hitting coaches, like Kevin Long, who emphasized the home run. This new strategy could be exactly what Conforto needs to beat the shift, and help him reach his full potential.

While Conforto posted solid overall numbers in 2018, the full shift stifled his production to a degree. According to SIS’s data, the full shift robbed Conforto of six hits (though he did gain two from partials).

While that six may not seem significant on the surface, it drags his average down to .243 instead of .254. Small differences like this can make an impact over a course of a 162-game season where games are often won and lost by small margins.

And thanks to Conforto’s power and excellent eye at the plate, he still was very productive despite his low average. Conforto posted a 120 wRC+ with 28 homeruns in 638 plate appearances last season, and he also managed to get on base at a solid .350 clip because of his high walk percentage. Conforto took ball four in 13 percent of his plate appearances, which ranked 21st in the majors among qualified hitters.

The former first round pick has the power and patience to rank among the game’s elite. And now that he is fully recovered from the shoulder injury that cut his 2017 campaign short, the full shift is one of the few things that’s holding him back.

Conforto’s upside will be limited if he can’t adjust to the shift. And once teams realize that partial shifts aren’t effective against him, He will face more of a challenge as he will see more full shifts (he only saw full shift the opening weekend). Therefore, it is important that Conforto heeds Davis’ advice and starts driving the ball to the opposite field more often.