By Brandon Tew

Baseball in 2019 looks drastically different than it did five years ago. Now, hitters worry about launch angles and exit velocities. But this year’s efforts of Atlanta’s dynamic duo of Max Fried and Mike Soroka should worry Braves’ opponents.

Fried and Soroka lead the Braves rotation with 14 and 10 wins, respectively. They also sit among MLB’s best in a stat that tries to combine launch angles and exit velocities into a quantifiable stat for hard-hit balls. The pair of young arms rank second and third in lowest rate of barrels allowed among pitchers with at least 350 batted ball events this season, with Fried allowing them at a 2.6% rate (15 barrels allowed) and Soroka 3% (18).

MLB.com notes that the “barrel” classification is assigned to batted-ball events whose comparable hit types (in terms of exit velocity and launch angle) have led to a minimum .500 batting average and 1.500 slugging percentage since Statcast was implemented Major League wide in 2015.

To be Barreled, a batted ball requires an exit velocity of at least 98 mph. At that speed, balls struck with a launch angle between 26-30 degrees always garner Barreled classification. For every mph over 98, the range of launch angles expands.”

This stat helps quantifies the number of hard-hit balls on the bat’s “sweet spot.” With the optimal launch angle and exit velocity, the ball usually goes for a base hit.

Fried and Soroka minimize this with by allowing low launch angles. They rank second and third in the MLB in average Launch Angle with Fried at 3.5 degrees and Soroka at 4.9 degrees.

So how has this Atlanta Braves pair missed so many barrels? They accomplish this in slightly different ways.

How they do it

Fried, a smooth throwing lefty, uses his four-seam fastball and a wicked curveball to keep hitters off-balance. With a lot of late-life on his fastball, Fried creates weak contact even in favorable counts to the batter.

Soroka, a right-hander uses pinpoint command and a heavy sinker to induce weak contact. Soroka will throw his sinker at any time and keep hitters off of it with a slider away or four-seam fastball that comes up and in.

Their different approaches embody the shift in pitching over the past five years, with Fried putting emphasis on a high-velocity four-seamer and good breaking pitch while Soroka favors the old-school pitching combo of a sinker and slider. Soroka pitches to contact and keeps the ball down in the zone.

When you’re as adept at missing barrels as Fried and Soroka, you try to get ahead in the count and strike out batters or create soft contact, such as a weak ground ball. Both are great at producing ground balls. Soroka and Fried each have 53% ground ball rates, with Soroka ranking fourth and Fried sixth among ERA-title qualifiers.

As for any pitcher, it is always best when you’re pitching ahead in the count to keep batters on the defensive so they can’t sit on one specific pitch, in one particular zone. First pitch strikes are a vital part of getting ahead in the count. They each are above MLB average of 61%, with Soroka at 64.6% and Fried at 63.7%

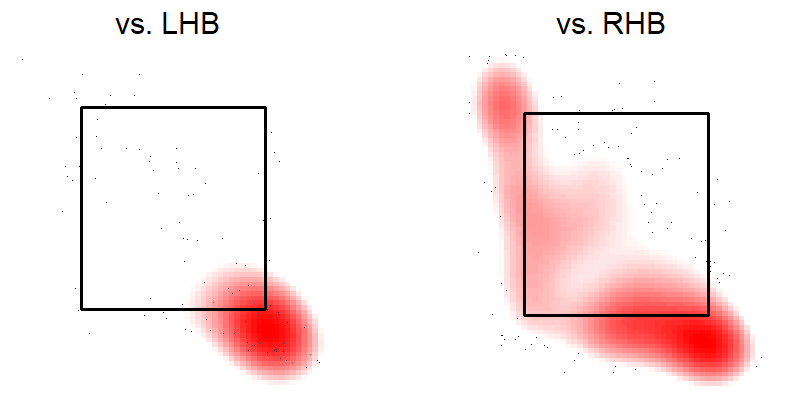

Soroka pounds the arm-side bottom right corner of the zone with his sinker. He does this all game long. When behind in the count hitters have no choice but to either swing and probably make terrible contact or take the pitch for a strike. Hitters constantly smash his sinker into the ground. It’s a pitch that either runs under the hands of a right-handed batter or down and away from a lefty. Soroka also has the command to work this part of the strike zone.

When he’s not throwing his sinker, he’s working the other side of the plate with his slider, throwing it down underneath the zone, making it almost impossible to square the ball up on this particular pitch.

Hitters are once again faced with the decision to swing and likely make a soft-contact grounder, or go fishing for a ball destined for the dirt. They’re hitting .136 when an at-bat against Soroka ends with this pitch. That ranks fifth-lowest in MLB among starting pitchers, behind Dinelson Lamet (.095), Justin Verlander (.112), Sonny Gray (.119), and Mike Cleveinger (.119).

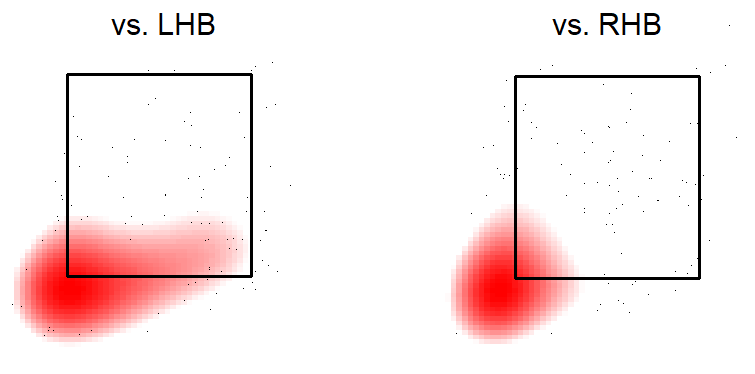

The heat map below shows how Fried utilizes his curveball to keep hitters guessing, while still throwing it in the zone often and inducing weak contact or missed swings. If hitters do connect, they generally swing over the top sending the ball darting towards the ground.

This also enables him to use his fastball more effectively. A fastball with so much late life keeps hitters from making great contact with the heater. When ahead in the count Fried can still be sporadic with his fastball command but he still stays inside the zone.

What lends to Fried’s remarkable knack for missing the sweet spot of bats or getting a swing and a miss is the tunneling of both of these pitches and how they look so similar to the hitter and have late action to them. Fried can occasionally lose his release point and miss arm side and high with his fastball or hang his curve but when he’s on, he’s excellent at throwing both of these pitches from the same release point. making it hard to pick up which pitch is coming towards the batter.

Why doesn’t Fried have as good of an ERA as Soroka? When hitters do get the ball in the air, they hit it out of the park. Fried’s home run to fly ball rate is 19%. Soroka’s is 8%. That may not entirely be Fried’s fault. Based on our expected stats (determined by the batted ball type, where the ball was hit, and how hard it is hit), Fried has allowed three more home runs than expected. Soroka has allowed three fewer.

This one-two punch will be key for Atlanta down the stretch in the NL East. For them to continue racking up wins, Fried and Soroka will have to keep missing Barrels.