BY ALEX VIGDERMAN AND JOHN SHIRLEY

Key takeaway: Weather has some predictable impacts, but maybe not at the scale that critics of dome-heavy quarterbacks think.

***

How much do weather conditions affect quarterback play?

This has been a hot topic following a tweet from the NFL’s Michael Lopez that pointed out that the list of the most effective quarterbacks over the last few seasons predominantly featured players whose home stadium was indoors. That prompted follow-ups from a few others, as well as Lopez himself.

We wanted to add a point or two to the conversation, starting with a blunt instrument and moving to a more nuanced approach. Think of it as “Weather Effects Two Ways.”

Does the Roof Make You On Fire?

We’ll start with just the impact of playing indoors versus outdoors.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that games played indoors have better passing numbers. The effect is quite small, though. Since the start of 2015, passes thrown indoors have been completed 2.6 percentage points more often. For what it’s worth, the numbers are the same when looking at only road teams (reducing sampling bias) or only late-season games (when playing outdoors is most likely to be a concern).

You might not notice the effect at a game level, but what about at a season level?

We took every pass over the last five seasons and split it on three dimensions: Indoor/Outdoor, Throw Depth, and whether the throw was outside the numbers.

Again, only road teams were used to prevent oversampling from teams whose home stadium is indoors. Taking the average completion percentage of each group (and including some smoothing from similar throws), we can find an expected completion percentage by throw distance, both indoors and outdoors.

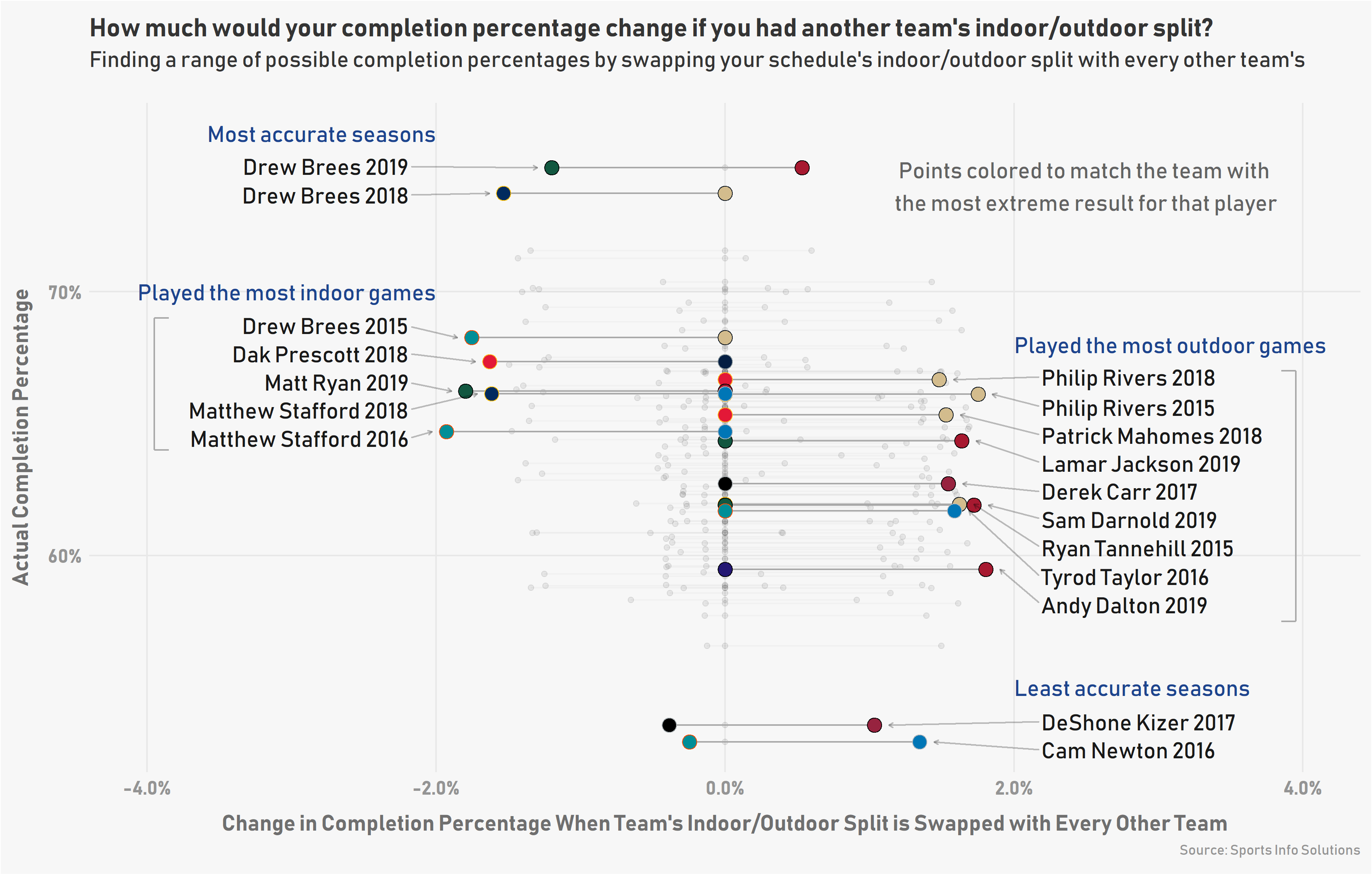

Using these indoor and outdoor expected completion percentages, we took each quarterback season with at least 400 attempts and pretended they played for every other team that season (at least in terms of their proportion of indoor games versus outdoor games).

In 2019, for example, every quarterback’s best performance would have come on the Falcons (81% of games indoors), and their worst performance would have come with either the Jets, Ravens, or Bengals (none of whom had an indoor game in 2019; the specific team would depend on what kinds of throws the quarterback made).

Here’s a visual of what those results look like.

What do we learn from this?

- If you switched between the most-indoor and most-outdoor schedules in any given season, quarterbacks’ completion percentages would change by at most two percentage points up or down

- Quarterbacks who tend to play indoors (hello NFC South) are operating at the high end of their range of outcomes

- This is not the best way to think about the effect of weather. Philip Rivers, Derek Carr, and Ryan Tannehill haven’t exactly played in adverse weather conditions, but they have played a very high percentage of their games outdoors.

Let’s take things in a different direction, then, and focus on the actual weather conditions, not just whether the quarterback got his daily dose of Vitamin D.

How Much Does Weather Really Matter?

Weather effects on a player’s performance are talked about quite a bit, but generally in an anecdotal way with no underlying data. How many times do you hear about a quarterback prospect needing a strong arm to play in the northeast during every draft process?

Similarly to indoor/outdoor effects on QB play, weather definitely plays a role, albeit a relatively small one.

To determine this we took pass attempts from road teams playing outdoors over the past four seasons and modeled a relationship between completions and throw depth, whether the throw was outside the numbers, apparent temperature, and whether there was significant precipitation present.

Apparent temperature accounts for wind speed, humidity, and air temperature. Significant precipitation is defined as any time the precipitation intensity was greater than or equal to 0.25 mm/hr (this accounts for the top 25% of throws with any level of precipitation). These two weather effects were found to be statistically significant within our model over the past four seasons.

This weather-adjusted expected completion model was then compared to a simple model that only accounts for throw depth and whether the throw was outside the numbers. By comparing the two models, we can determine how much weather plays a role in the passing game and which quarterbacks were most affected.

2019 QBs Most Negatively Impacted by Weather (min 200 Attempts)

| Player | Expected Comp% | Weather Adjusted Expected Comp% | Difference |

| Sam Darnold | 64.6% | 63.3% | -1.3% |

| Patrick Mahomes | 64.9% | 63.9% | -1.0% |

| Tom Brady | 66.0% | 65.2% | -0.8% |

| Aaron Rodgers | 64.0% | 63.2% | -0.7% |

| Russell Wilson | 63.1% | 62.4% | -0.7% |

2019 QBs Most Positively Impacted by Weather (min 200 Attempts)

| Player | Expected Comp% | Weather Adjusted Expected Comp% | Difference |

| Matt Ryan | 65.2% | 66.9% | 1.7% |

| Jacoby Brissett | 65.5% | 67.1% | 1.6% |

| Matthew Stafford | 61.2% | 62.6% | 1.4% |

| Drew Brees | 67.6% | 68.8% | 1.2% |

| Kyler Murray | 66.3% | 67.5% | 1.2% |

Unsurprisingly, a quarterback who played the majority of his games in the northeast, Sam Darnold, topped the list of players most affected by weather conditions. On the other side of things, we see a list of quarterbacks who played most of their games indoors as the most positively affected by weather conditions. However, the overall effect from weather is fairly small either way.

The Big Picture

Regardless of the method used, we see that having great or terrible weather over the course of a season can modulate a quarterback’s completion percentage by one or two percentage points. Michael Lopez found something similar, but also noted that the indoor/outdoor effect is larger than that of home field advantage, which has some interesting ramifications on things like point spreads.

Given these results, it seems a player’s typical weather conditions aren’t likely to be a big deal from season to season. The effect can of course accumulate, as in the case of players like Drew Brees, who has spent his entire career in favorable weather between San Diego and New Orleans. Drop his completion percentage by one point over his career, keeping the same yardage per completion, and he loses just under 1,000 passing yards over his career. For guys like that it only matters in the context of all-time records and Hall of Fame discussions, and even then only as a minor point in a larger discussion.

The key point to keep in mind is that there are lots of variables that affect a player’s statistics beyond his talent, and we need to understand the scale and direction of those effects when trying to evaluate players. Weather has some predictable impacts, but maybe not at the scale that critics of dome-heavy quarterbacks think.